The term ‘feminism’ can be a scary and confusing word to some. For many, feminism can be the fight for true gender equality. By default, it can also mean that you support combating violence against women, being pro-choice, support women’s economic and educational empowerment, etc. The term is almost unrestrictedly interpretable and can be attributed to many fields such as politics, economics and sociology. Observing feminist literature, it becomes clear that there is no precise definition of feminism and that the belief system is as plural as wider society. However, many women do not want to be classified as feminists due to the uncertainty of the definition and the negative connotations surrounding the word.

In Lithuania, feminism is not a very popular term and especially the notion of admitting to being a feminist. Although there are many interpretations of feminism, from my perspective, many Lithuanians tend to associate it with laziness – envisioning a sexually unsatisfied woman with greasy hair unwilling to do domestic chores. Meanwhile, others take a more mocking tone and refuse to take the movement seriously. Although Lithuania is above the worldwide average for women’s rights, true gender equality is still not a reality.

Other countries, such as those in Scandinavia, gender roles might not be as well defined as in post-soviet countries as they were not as affected by the red era.

More than half of the women in Lithuania are university students and 70% of high school graduates are female. The first woman, Dalia Grybauskaite, was elected President of the Republic in May 2009. The index shows that Lithuanian women work in the formal economy more than most of their European counterparts (ranked 4th), and there are more women among scientists and engineers in Lithuania than anywhere else in the EU. The gender employment gap is two times lower than in Sweden and is nearly negligible.

Then why the need for feminism?

Although it could seem as women were politically well off, sadly the fight is both in the social and political level. Having been raised and surrounded by Lithuanian women, I can say that these are some of the strongest and wisest women in life as their pain endurance threshold is unfortunately but also luckily, unbelievably high. They place and maintain the foundation, they manage the household, work overtime, nurture their children whilst maintaining social beauty standards. They endure any inappropriate comment and fulfill any wish without a single murmur.

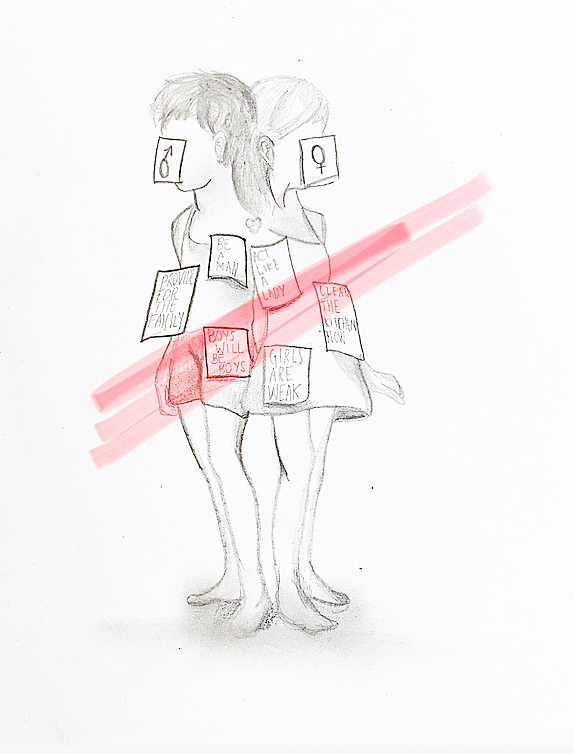

From a young age, gender roles in Lithuania become very clear. Girls are taught to be a caring mother, a proper woman, how to understand a man and how to please him. This is the main problem, and I dare to say that this a common cultural dilemma in many post-soviet countries. Other countries, such as those in Scandinavia, gender roles might not be as well defined as in post-soviet countries as they were not as affected by the red era. Politically and economically, women in Lithuania may seem to be well off, but they lack self-regard.

In Lithuania, women are expected to constantly express their femininity, to look and act a certain way, ingrained into them as an accepted norm from childhood. These norms do not leave much space for self-regard. Constantly the focus is on the needs of the man, how to look good for him and how to make him happy. For me, feminism is about self-love and about giving women a voice. I feel that every woman has something to say and should be able to use her voice. It is about self-regard and breaking free of these biased expectations.

Once we get to the core of feminism, we realise that men do not just profit from our inequality and get to pick the low-hanging fruit. However, Lithuanian men (and men in general) experience a great deal of implementation of one or another stereotype as well. We are used to believing that a true man is concerned with a wide variety of requirements: to keep the family, to be strong, emotionally strong, never to squander, to be defiled, to be empowered and healthy, to compete, to always be defeated.

Taking toxic masculinity out of politics and enabling women to have self-regard may bring a trickle-down effect that the rest of society needs.

Studies show that when these expectations are not fulfilled, men reach to other self-harming means such as suicide, alcoholism, smoking, crime, aggression, violence. It is clear that there is an urgent need to get rid of these gender expectations that fuels toxic masculinity, and in the long run, hurts men as well. The feminism I propose is the kind that gives women a voice, equal opportunities, destroys the gender stereotypes, and portrays self-love and acceptance to admit struggle.

What now?

As mentioned, feminism is a new term in Eastern Europe. Politically, there is not much to be done if the mentality does not change. The European Union played, and still plays, a key role in initiating and contributing to gender-mainstreaming policies in Lithuania, and it is safe to say that people in other EU countries set the example. However, I am trying to point out that feminism is not just about politics and the providing of equal rights, it is also a question of mentality.

Our political spheres are key to driving the process to not only providing legislation for gender equality but to put this ethos at the heart its institutional culture and functions. Taking toxic masculinity out of politics and enabling women to have self-regard may bring a trickle-down effect that the rest of society needs to change its mentality.

Average Rating