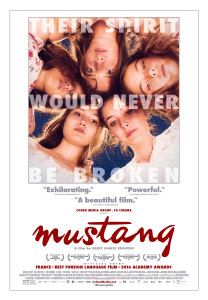

“Mustang”, a movie about young girls’ oppression in Turkey, has been nominated for the Oscars in the category “Best Foreign Language Film”. An interview with its director, Deniz Gamze Ergüven

All of these people that I’d met or run into this past summer told me that I should see Mustang – an epic tale of five sisters who live with their grandmother and uncle in a seaside village in Karadeniz, Turkey. I went to one of these old cinemas in Paris to watch it this October. After all those scenes where little laughter and giggles filled the theatre, I felt like there was this big knot in my throat. I was born and raised in Turkey, I have a sister as well, and those scenes seemed so familiar. After a point this knot got bigger, tears went down my face and I when looked through the audience, I saw this French man crying right next to me. Once the film was over I walked outside, and just in the corner of the cinema, I hugged my boyfriend and cried for minutes. I remember I kept saying “these things happen in Turkey and then people dare to ask me why we need feminism.”

The film is directed and co-written by Deniz Gamze Ergüven, a woman who was born in Turkey and moved to Paris when she was 6 months old with her parents. She completed her entire education in Paris yet has never broken her bonds with Turkey. I had to find this woman, the woman who left an elephant sitting on my chest, who stealthily told a story, a story about being a woman, a story about how conservative culture oppresses young girls and destroys their lives, yet there is hope to be found! I contacted Deniz Gamze and we met in a café in Paris back in October 2015. She was so familiar it didn’t feel like an interview!

Can you explain the development process of Mustang?

I wrote the scenario with my friend Alice Winocour in the summer of 2012. The story had a structure and mechanics, just like a clock. The script didn’t allow much change and new versions. Whenever we wanted to change something, it was as if the balance was broken. After graduating from La Fémis, I’ve written a script, but I couldn’t shoot it. That’s why I was so ambitious to start shooting, and to work with actors and actresses.

How did you pick the 5 artists for the roles of the sisters?

I thought about these sisters as one character, as if they had 5 heads, 10 arms and 10 legs, like a Lernaean Hydra. I worked with a casting director and tried different combinations for 9 months. For me the hardest part was distributing the roles. It was important to show the cross relationships within the group and also the group’s relationship. Plus they all needed to look similar. Some of them look like twins. When they first met each other they were observing one and other with surprise.

This is your first feature-length film. It collected so many awards and attention. Were you expecting this? The movie was nominated for the Oscars by France and not from Turkey, how do you feel about this?

To be honest, while I was making the film, the furthest part that I saw was the movie making it to Cannes. When we were at Cannes, all of the distributers who’ve bought the movie came to talk to me and not once did they mention “to how many places did they sell the film” but instead they talked about their feelings towards the movie. This really affected me. People from many different cultures have bought this movie, they were sensitive to the issue and they understood the story. The nomination process for the Oscars actually happened very spontaneously. A very powerful distributer from USA has bought the movie and told me that he wanted to have an Oscar campaign for this movie. Actually I was expecting it to be elected from Turkey, but it didn’t turn out that way. But I had this instinct about this movie making it to the Oscars. Then it got elected from France and it came as a surprise! This is a very big honour for me. Really.

I read the comments in Turkish social media after your first interview getting published in Turkish media such as “there’s no child marriage tradition in Karadeniz” or “another director in Europe who tries to make Turkey look bad.” What do you think about these critics? Do you believe that your movie realistically narrates the cultural structure of that area?

Since the first screening of the movie in Cannes critics of “this movie is not Turkish” had begun. This was strange for me, hearing this from people who did not even see the film. Do movies really belong to a nation? We are one of those countries that rarely sends movies abroad. When the situation is like this, then we are forced to look through only one window, as if we are responsible to narrate the entire reality of Turkey. When there’s such obligation then you cannot do what you actually would like to do. This movie, does tell some realities from Turkey. These are things that I have lived, I have seen. If the stories told in the movie are not real, why was I told exactly the same things when I was at the same age of Lale? I was playing with my cousins and I got on the shoulders of some boys, and I’ve got told the same accusations that Lale got! My reaction was to look down, to be embarrassed. This is a story that happened to me in Turkey. What is fiction in this movie is the part where Lale refuses this oppression of embarrassment and she breaks the chair on the terrace saying “these chairs have touched our asses, they are disgusting too.” This, of course, is not real. What Lale does there is something heroic. In Turkey girls are not raised to be heroines, they are raised to be well behaved and polite. Mustang is not a historical work. The reality I sought in this movie was the reality of a feeling, the feeling of being a woman. Does Mustang tell the feeling of being a woman? I think it does.

The concepts such as abuse of young girls, child marriage and insect are a big taboo. There’s a common perception such as “it would not happen in our family”, “someone I know would not do this” or “this is not specific to our country” where there’s a denial of the crime or an attempt to blame someone else. What do you think should be done in order to break this taboo?

What surprises me the most is that, I don’t mean small families but in big families, I don’t think I’ve ever come across one that this doesn’t exist. Our responsibility is to question and look into the reality. When you swipe the dirt under the rug, it does not disappear, on the contrary we should make it more visible. Not just as artists but as citizens, our duty is to question, to reflect on it and search for reality. As a filmmaker, I cannot close my eyes and pretend that these experiences of people don’t exist. Especially on issues like these, I don’t think I have the right to do that.

In the past couple of years the conversation around sexism in Hollywood has increased. What are your opinions on sexism in cinema?

Actually there has been a very fast change regarding this issue. In our school we were only 2 women in my class. For example there’s a position called “script supervisor” and it’s mostly women who are in these positions. They call them “script girl.” There’s a perception such as each job is more suitable for women or men. It’s as if women are being pushed away from jobs that require leadership. To be a director means that you have to fight and persist on your idea sometimes. And it’s so interesting; there are some women who say “I do not have this in my character.” There’s a perception as if women cannot have these characteristics.

Don’t you think these are actually gender stereotypes?

Of course they are and they exist so strongly! This exists in Hollywood as well but now people started to question it. Mustang screens intelligent girls as brave figures. We lack this in cinema! In the western world, women feel more equal yet they have so many things to say that are stuck in their throats. This movie portrays so much of what we live, what we want to say in an optimistic way that it appeals to Western or American women as well. This is beyond me or Turkey.

You were pregnant throughout the shooting of this movie, how did this reflect on the movie?

I learned about my pregnancy just one week before the producer quit the movie. I did not have the right to be stressed and not shooting the movie just because I’m pregnant was not a choice. I guess this situation gave me some kind of calmness. When the producer left the movie, I was basically dead for the team. The movie did not exist, everything was over. And everybody pitied me, saying “look what happened and the poor thing is pregnant.” I guess when I accomplished to put everything back on track nobody dared to mess with me. The pregnancy, holding everything together, me being persistent, all of these created a different mood for the team.

I gave birth on the same day that we learned about the murder of Özgecan Aslan [20-year-old student who was brutally murdered by 3 men as she resisted rape in February 2015 in Turkey.] I was disconnected from the world for 24 hours and the next day when I looked at the news, I saw Özgecan. I will remember that photo forever. During those hours as a woman I was experiencing giving birth and her experiencing that affected me a lot. Just 2 days after birth I started working again, I never stopped. I finished this movie cheek to cheek with my child. The first 3 months after birth is like the continuation of pregnancy, he was just like a little monkey attached to me. We finished the post-production together.

Can we say that you’ve given birth to two things at the same time, your child and your movie?

Yes, I always talk about it like this as well, they’re twins! I gave birth during the sound editing of the movie. I was going to work with someone I don’t know and we were supposed to meet in a café yet I realized I couldn’t get out of the apartment. I was just out of the hospital 2 days ago, I have a crying and hungry baby and I myself don’t even know what to do! So I called him and invited him to come over. When I opened the door he saw me with a 2 day old baby in my arms. It’s the first time we meet and there I am breastfeeding. I don’t think he ever saw me without my baby attached to me.

Many find similarities between Mustang and Virgin Suicides. How do you respond to that?

Yes this question is asked many times. Yet they are similar but I was not inspired by it. I read the book and I watched the film but Mustang is my story. My family, just like in Virgin Suicides, is a women’s family. Especially when I look at the photos of my mother’s generation, I see girls in long hair, if I was to describe them romantically they are like a girls’ nebula. I also have one interesting story from my childhood. One summer we were at our family house and other relative girls arrived as well. Blonds, brunettes, we were all together like in a coop. A neighbor boy has asked our friend the phone number of the house and our friend asked “for which one?” and he responded: “doesn’t matter, just any one of them.” I still remember this memory. This approach of not being able to differentiate between the girls, this perception of “what difference does it make, it’s just a girl.” This memory I have is a very common point with Virgin Suicides.

We see an #OccupyGezi t-shirt being locked in a closet with the rest of the “objectionable and dangerous” objects in the movie. What was your experience of Gezi Park protest in Turkey? Do you have hope for the future of Turkey?

My eyes are always on Turkey. I don’t lose my sleep over France but I do over Turkey. When the Gezi Park Protests began, I was in Los Angeles, and immediately I flew to İstanbul. When the police attacked to empty the park, I was there, standing on the stairs of the park. Not being there, was not an option for me. The ideas that women established there were very exciting, revolutionary, and even more modern than of the western cultures. There were ideas that got transferred from one occupy movement to another. New critical perspectives were created on capitalism, ecology and feminism.

But of course, after that, it was like we were beaten with wet wooden sticks. It was as if we really lost a big combat. Now we are in a period in Turkey where people are afraid to and therefore cannot really express their opinions publicly. The public conversation is suppressed. We are in a period where our main values are shaken, from democracy to secularity. It’s very difficult to see the future of Turkey. The geopolitical situation of the country is very sensitive.

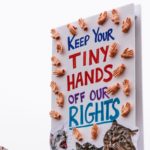

It’s difficult to say if I am hopeful or not. Yet what I find truly healthy and hopeful is that there’s always an amazing reaction whenever something negative happens. For instance whenever they do or say something conservative about women in Turkey, the feminists react very collectively and powerfully.

What are your plans for your upcoming movies?

Each day there’s a new project coming up. I’m in a period just like when Mustang was developing. There are some cars on the street and I don’t know which one is going to pass the other one. Alice and I are writing a new script which takes places in İstanbul and my Los Angeles project is on discussion again, it’s becoming a very strong possibility.

*All images are courtesy of Cohen Media Group. The last picture was taken by freelance journalist Sophie Janine

“Mustang” Türkiye’deki genç kızlara uygulanan baskıyı anlatan, “En İyi Yabancı Film” dalında 2016 Oscarlarına aday olan bir filmdir. Filmin yönetmeni Deniz Gamze Ergüven ile bir röportaj.

Mustang. Türkiye’nin Karadeniz bölgesinde bir sahil kasabasında geçen, babaanneleri ve amcaları ile birlikte yaşayan 5 kız kardeşin destanı. Türkiye’de doğmuş, 6 aylıkken ailesiyle Paris’e taşınmış, tüm eğitim hayatını Paris’te tamamlamış; ancak Türkiye’den hiç kopmamış Deniz Gamze Ergüven’in yönettiği ve senaryosunu ortak yazdığı bir film. Birçok festivalde ödül alan ve Fransa’dan Oscar aday adayı olan Mustang’in yönetmeni Deniz Gamze Ergüven, hiç çaktırmadan, öyle derin bir hikâyeyi göğsümüze oturtuyor ki! Kendisiyle Paris’te bir kafede, bir röportaj gerçekleştirmekten öte, 1 buçuk saat boyunca dertleştik. İşte bu samimi sohbeti aktaracağım şimdi sizlere.

Mustang’in oluşum sürecini anlatabilir misiniz?

Senaryoyu 2012’de Alice Winocour ile birlikte tek bir yaz döneminde yazdık ve bitti. Hikâyenin küçük bir saat gibi, mekaniği ve çok net bir yapısı olduğu için fazla değişikliğe, yeni versiyonlara tahammül eden bir senaryo değildi. Ne zaman bir şeyi değiştirsek sanki bir denge kırılıyor, bozuluyor gibiydi. Sinema eğitimimi La Fémis’te tamamladıktan sonra bir senaryo yazdım; ama onu çekemedim. O yüzden çok büyük bir hırsla, çekim aşamasına geçmek, oyuncularla çalışmak istiyordum.

Filmde 5 kız kardeşi canlandıran oyuncuları nasıl seçtiniz?

5 kız kardeşi ben hep tek bir karakter gibi, 5 kafası, 10 kolu, 10 bacağı olan bir hidra gibi düşündüm. 9 ay boyunca bir cast direktörü ile çalıştım ve farklı kombinasyonlar denedim; fakat en zor kısım rolleri dağıtma kısmıydı. Grubun içinde belirli dengelerin oluşması gerekiyordu. Hem kendileri arasındaki çapraz ilişkileri, hem grup ilişkisini yaşatmamız gerekiyordu, ayrıca fiziksel benzerlik olması da gerekiyordu. Bazıları ikiz gibi duruyor, ilk tanıştıklarında birbirlerine şaşkınlık içinde bakıyorlardı.

İlk uzun metrajlı filminiz bu kadar ödül aldı ve ilgi gördü. Bunu bekliyor muydunuz? Filmin Türkiye’den değil de Fransa’dan Oscar için aday gösterilmesi konusunda hisleriniz neler?

Açıkçası, ben filmi yaparken ufukta görebildiğim en uzak yer filmin Cannes’a gitmesiydi, ondan sonrasını göremiyordum. Cannes’da filmi satın almış olan dağıtımcılar teker teker gelip benimle konuştular. İnsanlar “filmi şu kadar sattık” gibi cümleler kurmak yerine filme karşı hislerini anlatıyorlardı. İşte bu bana çok çarpıcı gelmişti; çünkü farklı kültürlerden insanlar hem filmi satın almışlardı, hem konuya hassaslardı, hem de hikâyeyi anlamışlardı. Oscar adaylığı ise aslında çok spontane gelişti. Oldukça güçlü bir dağıtıcı filmi satın aldı ve Cannes’da gösterildiği ilk akşam bu film için Oscar kampanyası yapmak istediğini söyledi. Ben doğal olarak Türkiye’den seçileceğini düşünüyordum. Olmadı. Sonra Fransa’dan seçildi ve bu o kadar büyük bir sürpriz oldu ki. Çok büyük bir onur gerçekten.

‘Fransız filmi mi? Türk filmi mi? Hayır, bu benim dünya üzerine bakışım.’

Türkiye’de yayınlanan ilk röportajınızdan sonra sosyal medyada bazı yorumlar okudum. “Karadeniz’de çocuk yaşta evlenme geleneği yoktur” ya da “Avrupa’da Türkiye’yi kötü göstermeye çalışmış bir yönetmen daha” gibi yorumlar bunlar. Bu yorumlar hakkında ne düşünüyorsunuz? Filminizin hikâyenin geçtiği bölgedeki kültürel yapıyı gerçekçi aktardığını düşünüyor musunuz?

Filmin Cannes’da gösteriminden itibaren garip bir şekilde “bu film Türk filmi değildir” diye bir tepki başladı. Bu bana çok ilginç geldi. Filmi hiç görmemiş insanlardan da bu tepki geldi. Filmler illa bir milletin mi olmalı? Biz yurtdışına az film çıkaran ülkelerdeniz. Böyle olduğu zaman sanki tek bir pencereden bakmalı, bütün Türkiye’nin yüzünü gösterecekmiş gibi mesuliyet almalıyız. Böyle olunca da istediğiniz şeyleri yapamıyorsunuz. Bir de Türkiye’de sinemada çok büyük bir natüralizm, yani gerçeğe benzerlik kaygısı var. Mustang kendi estetiği, kendi coğrafyası olan bir film; destan gibi anlatılmış bir kurgu. Evet, bütün sahnelerin temel taşları, durumlar gerçek; ama diyaloglardan, senaryoya, estetik seçeneklerden, oyuncu seçeneklerine kadar hepsi natüralizmden uzak duran şeyler. Bana şu soru çok saçma geliyor: Fransız filmi mi? Türk filmi mi? Hayır, bu benim dünya üzerine bakışım. Bir de tüm bunlardan sonra ben Türk müyüm, Fransız mıyım tartışması başladı. Bu da beni gerçekten üzen bir şey. Benim bütün ailem ve aile anılarım Türkiye’den. Ben de aynen Lale gibi, iki kuşak kadınlardan oluşan bir ailenin en küçüğüyüm. Nereden bakarsak bakalım, film Türkiye’nin bir takım gerçeklerini ortaya koyuyor. Ben Karadeniz’de görüştüğüm jinekologlar bekâret testlerini anlattıklarında “gerdek gecesinde” çalışmayan bir televizyon gibi paketlenerek hastaneye getirilen gelinlikli kadınları anlattılar. Anlattıkları sadece bir defa yaşanmış hikâyeler de değil. Filmde anlatılan hikâyeler gerçek değilse, ben Lale ile aynı yaştayken kuzenlerimle erkeklerin omzuna çıktığımda bana aynı lafların söylenmesini, aynı ithamların yapılmasını nasıl açıklayacaklar? Bu sahneyi kendim yaşadığımda benim tepkim utanmak, bakışlarımı kaçırmak ve başımı öne eğmek idi. Bu benim Türkiye’de başıma gelmiş bir hikâye. Kurgu olan ise Lale’nin bu hikâyeyi, bu utanç baskısını yaşadıktan sonra terastaki sandalyeleri kırıp “bu sandalyeler de kıçımıza değdi bunlar da iğrençtir o zaman” demesi. Bu elbette gerçek değil. Lale’nin davranışı kahramanca bir şey. Türkiye’de kızlar, kahraman değil, terbiyeli, edepli olmak için eğitiliyorlar.

Kız çocuklarının sömürülmesi, çocuk yaşta evlilik, ensest gibi konular büyük bir tabu. “Bizim ailede olmaz, tanıdığım biri bunu yapmaz ya da bu bir tek bizim ülkeye mahsus bir sorun değil” gibi suçu kabullenmeyen veya üstünden atmaya çalışan bir algı var. Bunun yıkılması adına ne yapmak gerekli?

Aslında beni şaşırtan, çekirdek aileleri kastetmiyorum; ancak geniş bir aile içerisinde böyle bir vakanın yaşanmamış olduğu bir durum ile karşılaşmadım. Problemlerin üstünü kapatmak ile olmuyor, tam tersine, görünür kılmak gerekiyor. Sadece sanatçı olarak değil, vatandaş olarak da görevimiz sorgulamak, düşünmek, gerçekleri aramak. Bir sinemacı olarak da gözlerimi kapatıp insanların deneyimlerini görmezden gelemem. Özellikle böyle sorunlarda bunu yapmaya hakkım yok diye düşünüyorum.

‘Mustang zeki ve cesaret figürü kadınları sahneliyor.’

Son yıllarda Hollywood’da cinsiyetçilik sıkça konuşulur oldu. Sinemada cinsiyetçilik konusunda düşünceleriniz nelerdir?

Aslında bu çok hızlı bir şekilde değişmeye başladı. Daha bir sene önce yapımcıma Amerikalı bir ajans “ben kadın yönetmen almıyorum, onlar gişe yapmıyor” demişti. Ünlü yönetmenler arasında gerçekten çok az kadın var. Bizim okulda benim dönemimde sadece iki kadındık. Mesela devamlılık takibi pozisyonu var genelde kadın oluyor bu kişiler ve onlara “script girl” deniyor. Bazı meslekler daha çok kadınlara ya da erkeklere yönelikmiş gibi bir algı var. Liderlik gerektiren mesleklerden kadınlar itiliyor gibi. Yönetmen olabilmek bazen kavga edebilmek, fikrinde diretebilmek demek. İlginç bir şekilde kadınlar da “bizim karakterimizde bu yok” diyebiliyorlar. Bu özellikler genelde kadınlarda yoktur gibi bir algı var.

Bunlar cinsiyet rollerindeki kalıp yargılar değil mi sizce?

Kesinlikle öyle ve bunlar çok güçlü bir şekilde mevcut. Bu Hollywood’da da var ve artık sorgulanmaya başlıyor. Mustang zeki ve cesaret figürü kadınları sahneliyor. Bu o kadar büyük bir eksik ki! Batı’da kadınlar kendilerini daha eşit hissediyorlar; ama onların da boğazına sıkışmış bir dolu şey var. Film yaşadığımız onca şeyi, söylemek istediklerimiz ve söyleyemediklerimizi iyimser bir şekilde sahnelendiği için Batılı kadınlara da hitap ediyor. Bu beni de, Türkiye’yi de aşan bir boyut. İnsanların filmi sahiplendiği şekil beni çok aşıyor. Mustang’ın konusu kadın olmak ve Türkiye’de kadın olmak. Sanat ve sinema tarihinde dünyayı erkeklerin gözünden görmeye alıştık. Kadınları obje olarak görüyoruz. Bir kadın bakışına alışık değiliz, bir kadının obje değil süje olmasına hiç alışık değiliz.

Sizce kadın hikâyelerini, kadın yönetmenleri sinemada daha görünür kılmanın yolu nedir? Bu görünürlüğün, sinemanın gücünün, kadın hakları konusunda etkisi ve önemi nedir?

Sinema fikirleri kırmak ve bir takım fikirleri öne çıkarmak için o kadar önemli bir mecra ki! Şu an bir virajdayız. Kadınlar artık sinemayı, kamerayı sahipleniyorlar, bir şeyler yapmaya başlıyorlar. La Femis’ten bildiğim, benden küçük olan ve birkaç sene sonra film yapacak kadınları tanıyorum. Bir de artık yolu açmaya başlayan kadın figürler var.

‘Mustang kadın olma hissini anlatıyor.’

Filmde özdeşleştiğiniz bir karakter var mı? Lale aracılığıyla kendi genç kızlık isyanınızı konuşturduğumuzu söyleyebilir miyiz?

Evet; ama tavır olarak benim o yaşlardaki tepkim hiçbir şey söylememekti. Aslında en çok Selma’ya benziyorum; sinekten korkan, gıkı çıkmayan Selma’ya. Bir derece de Lale ile de benziyorum; ama başka nedenlerden ötürü. Benim sinema hayatım çok uzun bir yoldu. İlk başta ben de evden terliklerle kaçan Lale gibi, terliklerimle yola çıktım. Bir dolu şeyi hazırladım ve birden hepsi birleşti ve filmim doğdu. Filmin galasında filmi izlerken son sahnede Alice ile birlikte ağlamaya başladık. Orada da başka bir şeyi, bizim hikâyemizi anlatıyorduk çünkü. İşte sinema böyle bir şey. Sinemada bazen bir takım gerçekler bükülüyor, tarihi iki karakter, tek bir karakter oluyor ve bu duruma bir netlik getiriyor. Hikâyeye akış sağlıyor. Mustang tarihi bir çalışma değil. Aradığım gerçek; hissin gerçekliği. Mustang kadın olma hissi nedir ve onu anlatıyor mu, anlatmıyor mu? Bence anlatıyor. Peki, gerçekçi mi? Hayır değil.

‘Hamile olduğumu ilk yapımcı filmi terk etmeden bir hafta önce öğrendim.’

Çekim boyunca hamileydiniz, bu sürecin filme yansıması nasıl oldu?

İlk filmimi yapana kadarki dönem, benim için biraz zor bir dönemdi. Hayatımı tam düzene oturtmadan kendime aile kurma hakkını tanımıyordum. Aslında filmin çekimleri bittikten birkaç hafta sonra evlenecektim; ancak ilk yapımcı filmi terk edince çekimler ertelendi. Düğünüm de bu yüzden çekim dönemine denk geldi. Çekimlerden kaçıp İstanbul’a gidip evlendim, sonra İnebolu’ya tekrar koşuşturdum. Hamile olduğumu ise ilk yapımcı filmi terk etmeden bir hafta önce öğrendim. Hiçbir şekilde stresli olmaya hakkım yoktu. Hamile olduğum için filmi yapmamak gibi bir durum da söz konusu değildi. Sanırım bu durum ilginç bir soğukkanlılık verdi bana. Yapımcı gidince Türkiye’deki bütün ekip için ben bitmiştim. Film yoktu. Her şey bitmişti. Bir de herkes “ah, vah, bir de kadın hamile” diye üzülüyordu. Bütün bu olan bitenden sonra ayaklanıp, filmi rayına oturttuğum zaman artık kimse sataşmadı. Hem hamilelik, hem bütün her şeyi bir arada tutmak, hem benim kararlılığım; hepsi birleşince farklı bir saygı oluştu tabi insanlarda. Doğumum ise Özgecan Aslan cinayeti ile aynı gün oldu. 24 saat boyunca dünyadan koptum ve sonra gazeteye bakınca Özgecan’ı gördüm. O fotoğrafı ebediyen hatırlayacağım. O saatler içerisinde bir kadın olarak ben doğum yaparken, onun böyle bir şey yaşamış olması beni çok şiddetli etkiledi. Doğumdan 2 gün sonra tekrar işbaşı yaptım, hiç durmadım. Çocuğumla yanak yanağa bitirdik bu filmi. Zaten doğumdan sonraki ilk 3 ay, hamileliğin devamı gibi, hep böyle bana yapışık küçük maymun gibiydi. Yapım sonrası dönemini beraber tamamladık.

Filminiz ve bebeğiniz, iki doğumu bir arada gerçekleştirdiğinizi söyleyebilir miyiz?

Ben de hep öyle anlatıyorum zaten ikizler diye. Doğumum ses montajı dönemine denk geldi. Montaj için tanımadığım biriyle çalışacaktım. Onunla bir kafede buluşacaktık ama gidemedim; 2 gün önce hastaneden çıkmışız, bebeğim var, ağlıyor, aç ve ben bile bilmiyorum ne yapacağımı. Aradım ve dedim ki “ben kafeye gelemem sen eve gel.” Kapıyı açtığımda onu kucağımda bebeğimle karşıladım. İlk defa tanışmışız, ben bir yandan bebeğimi emziriyorum falan. Zannediyorum ki beni hiç kucağımda çocuksuz görmedi. Montaj çalışmalarında böyle kucağımda bebeğim var, arada ağlıyor, altını değiştiriyorum, birisi sinirimi bozduğu zaman iyice altını açıyorum; bebek bezli sabotajların yaşandığı bir dönemdi.

Mustang ve Virgin Suicides arasında benzetmeler yapılıyor, bu konudaki yorumunuz nedir?

Bu soru çok sık geliyor. Evet, benziyor ama etkilenme durumu yok. Kitabı da okudum, filmi de seyrettim; ama Mustang benim hikâyem. Bizim aile gerçekten, Virgin Suicides’daki gibi bir kadın ailesi. Özellikle annemin kuşağından aile fotoğraflarında kızlar hep uzun saçlı, bir kız nebulasına benziyorlar. Örneğin bir yaz bizim aile evine diğer akraba kızlar da geldiler, evde kızlar olarak böyle kümes gibi bir ortamdaydık. Komşu bir çocuk bizim bir arkadaşımıza evin telefon numarasını sormuş ve arkadaşımız da “hangisi için” demiş, o da “herhangi birisi için” demiş. O zamandan beri aklımda kalmış bir anı bu. Bu kimin kim olduğunu ayırt edemeyen, “herhangi bir kız işte, ne fark eder” bakışı. Örneğin bu anı Virgin Suicides ile çok ortak bir nokta.

Filmde hem Erdoğan’ın hem de Arınç’ın kadınlar hakkında verdiği demeçler duyuluyor televizyondan, bu sahneleri yerleştirme sebebiniz neydi?

Film 2012 yazında yazıldı; ancak sonrasında gelişen durumlar elbette filmde yankı buldu. O sahneler vardı, ya da internet yasaklarına gönderme olarak bilgisayarın kaldırıldığı sahne var. O dönem bir dolu şey yasaklanıyordu. Bu sahnelerde, dönemsel durumun da bir yankısı var elbet.

‘Türkiye’de toplumsal konuşma tamamen bastırılmış bir noktada.’

Filmde “sakıncalı ve yoldan çıkaran” birçok eşya ile birlikte dolaba kilitlenen #DirenGeziParkı t-shirtünü görüyoruz. Türkiye’de Gezi Parkı eylemleri ile birlikte yükselen sivil direniş hakkında ne düşünüyorsunuz? Türkiye’nin geleceğinden umutlu musunuz?

Türkiye’yi yakından takip ediyorum. Bu sene farklıydı tabii, hamileydim, uçağa binemedim; ama ondan önce ayda bir ya da daha fazla, iş veya aile durumu gereği hep gidip geliyordum. Fransa çok uykumu kaçırmıyor; ama Türkiye kaçırıyor. Gezi direnişi başladığında Los Angeles’taydım; atlayıp geldim Gezi’ye. Gezi Parkı boşaltıldığında o merdivenlerin üzerindeydim. Orada olmamama imkân yoktu. Kadınların orada doğurduğu fikirler çok heyecan verici, devrimci, Batı’dan çok daha modern fikirlerdi. Bir “occupy” hareketinden öbürüne sıçrayan yeni fikirler de vardı. Kapitalizme, ekolojiye, feminizme yeni bir bakış vardı. Gençliğin, yaşadıkları toplumun içerisindeki her konuyu zekice sorgulayabilmeleri çok heyecan vericiydi. Ondan sonra tabii ıslak odunla dövülmüş gibi olduk. Gerçekten bir mücadeleyi kaybettik gibi oldu. Şimdiyse Türkiye’de insanların fikirlerini açıkça konuşamadığı, her gün daha çok korktuğu, garip bir dönem yaşıyoruz. Şu an olup bitenlerden dolayı, toplumsal konuşma tamamen bastırılmış bir noktada. Laiklikten tutun demokrasinin temel taşlarına kadar her şeyin yerinden oynadığı bir dönem. Türkiye’nin geleceğini görmek çok zor. Tekrar seçime gidiyoruz, bir yandan iç savaş çıkıyor, ülkenin jeopolitik durumu inanılmaz derecede hassas. Umutlu muyum, umutsuz muyum bilemiyorum. Fakat sağlıklı olan bir şey var ki o da ne zaman negatif bir şey yaşasak tepki çok yüksek.

Bundan sonraki filmleriniz için planlarınız nelerdir?

Her gün yeni bir proje doğuyor açıkçası. Şu an tam Mustang’ın ortaya çıktığı döneme benziyor. Yolda birkaç tane araba var, hangisi öbürünü sollar ve geçer bilmiyorum. Alice ile İstanbul’da geçen bir senaryo yazmaya başladık. Ayrıca benim Los Angeles projem tekrar gündeme geliyor ve çok güçleniyor.

Los Angeles projeniz nasıl bir senaryo?

1992 Los Angeles olaylarını, Afrika kökenli siyahîlerin ayaklanmalarını anlatan bir kurgu. Ben sinema okumadan önce tarih okudum. Bu hikâyeyi ben yaşamadım, oralı değilim ancak gerçeklere hâkim olabilmek için bir tarihçi gibi her şeyi araştırdım. 3 sene boyunca orada olabilmek için elimden geleni yaptım. Radyoda, televizyonlarda geçen haber kayıtlarına ulaştım, onları dinledim, seyrettim. Hikâyedeki polislerin, çetelerin kafasının içini tanımak, nasıl düşündüklerini anlayabilmek, gerçeklerin nerede olduğunu bilip, onları kırabilmek için Los Angeles Polis Departmanı ile devriyeye çıktım, çetelerle görüştüm

*Tüm görseller Cohen Media Group’a aittir. Son iki fotoğraf gazeteci Sophie Janinet tarafından çekilmiştir

Average Rating