In this article I explore period tracking apps from a feminist perspective. I argue that through the designs and data collection they reflect and perpetuate, even if unintentionally, heteronormative notions of gender and sexuality.

Periods and its tracking are a normal part of life – it can help to stay in control. To do so, a sheet of paper could be used, but I bet most of my contemporaries use period tracking apps. It seems like a no-brainer: most of the time it’s next to you and you can log your period or check when it’s due. Moreover, for some people tracking mood and symptoms might help to better plan their activities around menstruation.

However, while I’ve always felt that period tracking apps have strong gender connotations, I’ve never analysed its problematics. There’s another thing I hadn’t considered until recently – the data these apps obtain. Hence, in this article I’ll argue that period tracking apps tend to reflect, even if unintentionally, gender stereotypes and then will move to the question concerning our data use and its heteronormative implications.

FLOWERY, PINKY DESIGNS AND GENDER ROLES

Until I read this article, I didn’t know how to describe that dominant period app colour palette. It’s millennial pink. While to really understand why these colours are chosen, one should interview app designers, it’s rather clear that it’s far from the actual blood colour.

Will app developers be willing to create a really inclusive and menstruator-friendly period tracker that doesn’t reduce women’s lived experiences to reproduction?

Interestingly, Epstein et al. (2017) have shown that pink and flowers aren’t that desirable – it’is stereotyping and can be a source of shame in front of other people. Why, then, is pink it so prevalent? One of the possible answers is that the way apps are created reflect the app designers behind the app. In this case, – mostly men and their perception(s) of menstruation as inherently feminine matter without acknowledging the variety of gender roles and personal preferences performed by the menstruators.

It’s not my intention to argue about personal design preferences as it’s no concern of mine, but I do think it can and should be subjected to critical examination. This allows to understand ways in which menstruation and menstruators are framed across different platforms and social settings. Currently, the discourse is mostly simplistic and deterministic.

(BIASED) DATA AND HETERONORMATIVITY

Data, which tends to be understood in numbers, is perceived as objective and neutral. Hence, it’s often presented as representing the ‘real’ life out there. As D’Ignazio and Klein argue, it definitely represents something but it’s not a complete picture. What you get depends on the question(s) you ask and, in the case of period tracking apps, it’s very heteronormative. As Delano notes, period tracking apps focus on pregnancy – getting pregnant or avoiding it. This further assumes not only that users can get pregnant, hence, are a healthy reproductive woman, but that they’re heterosexual as well. However, somewhat ironically, in an article Levy shares experiencing the inability of a period tracking app to ‘understand’ that she was pregnant and not on an ultra-long cycle. It seems, then, that apps are here to help to get pregnant but not always for supporting users during pregnancy. Clearly, period trackers, or rather AI, still have room for improvement in recognizing the vast variety of menstrual experiences.

This provides Facebook with some useful insights about us, such as, that we’re, probably, menstruating women.

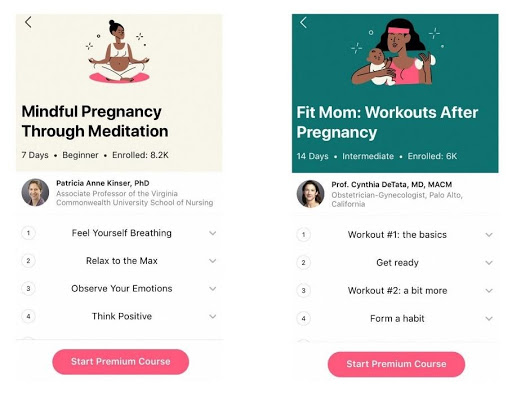

Why such focus on pregnancy? Targeting pregnant women is a good future investment for businesses. This is because pregnant women make new buying decisions and establish consumption patterns for the upcoming years. In other words, it is financially beneficial for the companies to collect data about pregnancy. Then companies can promote their own paid services. For example, Flo offers paid courses on being ‘Fit mom’ or on ‘Mindful pregnancy through meditation’.

Additionally, period tracking apps might share data with third parties, such as Facebook. Research conducted by Privacy International has revealed that data can be shared even before we agree to do so. For example, period tracking app Maya has been found to notify Facebook when it’s opened and it happens before sharing is allowed (as of September 2019). This provides Facebook with some useful insights about us, such as, that we’re, probably, menstruating women. This is a serious privacy concern and, furthermore, it demands a question of how that shared data is used. Obviously, for personalised ads.

This is not to say that we should always dislike personalised ads, but the question is under what conditions we get them. Medical data is extremely sensitive and should be handled with utmost care. Also, if pregnancy is so profitable and, thus, period tracking apps are incentivised to frame them in relation to pregnancy, where does it leave women who simply don’t care about pregnancy? Women who track their periods for menstrual health reasons? Will app developers be willing to create a really inclusive and menstruator-friendly period tracker that doesn’t reduce women’s lived experiences to reproduction?

WHAT’S NEXT THEN?

What could be done to challenge and resist these highly gendered aspects of period tracking apps? To start off, start filling up the data gaps and employing a data feminism approach. Data feminism is an intersectional approach towards data that considers how data science can be used to reinforce existing inequalities and how, then, data science can be used to challenge them. Finally, it believes in co-liberation – an idea that unequal power relations are the basis on which social problems prevail. In terms of designs, there’s no need to be reductive and completely dismiss the hegemonic palette, but pink shouldn’t be the only option. Maybe if we all, intentionally, choose period tracking apps with alternative and non-stereotypical designs, period tracking app creators will be encouraged to provide us with greater variety that reflects the reality of menstruators.

![Abortion rights in Croatia 4 years later – Pravo na pobačaj u Hrvatskoj 4 godine poslije [EN/CRO]](https://www.youngfeminist.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Safe-Abortion-Day-150x150.png)

[…] to an extent. The above-mentioned advantages are certainly of value. Several users, however, are increasingly pointing out certain fundamental shortcomings that allegedly (and […]